YC, Ultras, NYC, Fusion

Hello again friends,

A number of you have mentioned to me that I’ve been delinquent with my latest update. You’re right, it’s been 9 months! The year has flown by.

I’ll try and recap the highlights of everything that I’ve been up to since then. Since this update tries to capture 9 months worth of material, it's longer than most. Future posts will be shorter but deeper. As always, send me your best book recs.

USDR

Beginning in January, I started working with the US Digital Response as part of the Health Program, which I discussed briefly in my last update.

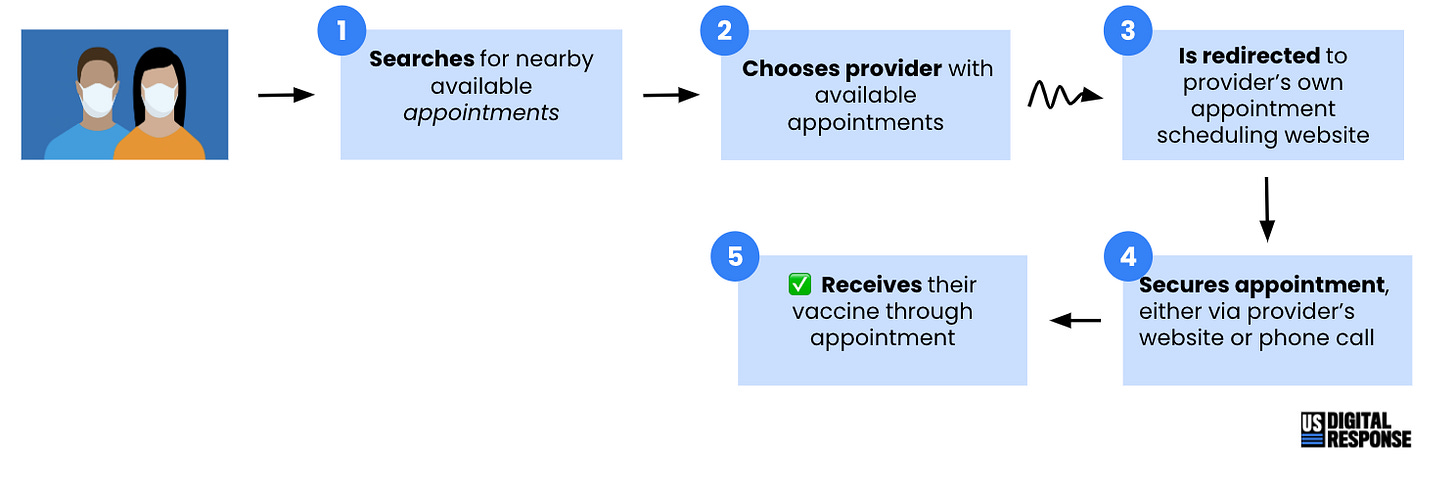

As we worked with various state and local governments, we realized that the biggest problem was helping people find appointments.

In the days before widespread vaccine availability, finding an appointment was quite tricky. States had their own guidelines around eligibility, inventory would shift minute-to-minute, and each medical provider would have their own independent inventory system.

The result was that there was no single trusted source to find appointments. Instead a whole host of unofficial twitter bots and vaccine scrapers designed to help people get vaccines. States wanted to offer similar functionality backed by a '.gov' domain, but most didn't have the technical depth to provide that sort of API.

So, we went about creating a single appointment availability API across a number of different sources (Albertsons, CVS, CDC, etc) which we called UNIVAF (universal vaccine appointment finder). We sought to provide minute-by-minute updates about where an individual could find a vaccine.

The API is still live and functional, you can find the github repo here. Most of the credit here goes to Rob Brackett at USDR, who really spearheaded the effort regarding scrapers the data format, and the schema. I spent time setting up the AWS accounts with some fresh Terraform.

I think our impact could have been much greater if we'd moved a little bit earlier on the API. We rolled out the initial functionality in early April, when supply had just started to surge in the US.

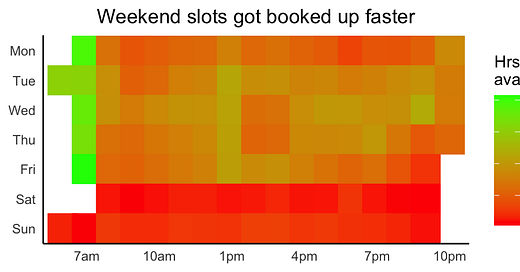

That said, a few states are using this infrastructure now, and data scientist Jan Overgoor put together some analysis using the data, which I haven't seen anywhere else.

It might seem obvious that people have a harder time making weekday appointments… but vaccine centers often missed that. Having actual data will help us do better next time.

No doubt it will be part of the continued learnings from the pandemic in the years to come, and as new vaccines are developed.

YC S21

This summer I joined YC as a Visiting Group Partner. It's undoubtedly been one of the best learning experiences of my career. I worked with Michael, Tim, and Diana to help about 100 startups through the batch.

I had a bunch of observations about little things that I learned during the course of the batch. My top few are here...

Structurally, YC is hard to beat – I don't think I'd want to be an investor at most firms, but YC is really different. Funding hundreds of companies (of tens of thousands who apply!) twice a year requires partners to be flexible and view businesses in a 'first principles' manner. The partners are largely optimistic, and have creative ideas for how a business could generate $100m+ in revenue.

Because of the structure, YC can do a lot of things traditional investors can't: fund competitors, review thousands of applications, take many many small bets, and make the difference between success and failure at a fragile time in a startup's life. YC's primary mission is to make more successful startups in the world, and there’s a lot of flexibility in how that can be achieved.

More startups could benefit from YC – from talking with friends, there's a common sentiment that YC is only worth doing if you can't raise money from VCs.

I don’t think that view is accurate. I've invested in a decent number of companies both in and out of the YC network. I'd say at least 50% of my investments outside of YC could really benefit by going through the program. YC's core value doesn't come from the money. Instead, it's the advice and the structure for running your company.

The program has gotten 10x better – when we went through YC in 2011, there were some special people there who would consistently give us great advice: PG and Sama immediately spring to mind. They would both give us the blunt feedback we needed to hear, while continuing to believe in us. But after demo day, things sort of ended.

Today, YC's goal is to support companies through IPO: that means helping you raise a Series A, helping you scale your company, and most importantly, helping you hire. Work-at-a-startup and HN job postings are hugely under-appreciated on that last point.

On the growth side, I've been pretty blown away by what Ali at YCC has created. It's a world-class program in how to run your company at scale. They bring in executives each week to help teach founders and leaders how to scale themselves. Most YC companies who hit Series A metrics should try and join the program.

The best partners can get to the 'crux' of the business right away – when I would watch some of the partners operate, I found some of them had fantastic ability to zero in on "what wasn't going well", even if they didn't know much about the business. This was an area I kept trying to continue to cultivate personally. It's harder to do without seeing a few hundred companies operate... but the more you see, the better you can pattern match.

There's a lot of other smaller lessons, things like:

the path to $100m in revenue is impossible to imagine if you've never done it, but blindingly obvious once you have

fundraising is the #1 thing that founders stress about, more than their company or customers (they should be focusing more on the latter)

founders always want benchmarks. providing these as a service (Lattice, Pave) is a great business to be in

building a hardware/hard-tech business is more possible than ever, but generally requires great fundraising

hiring is incredibly competitive right now

the best teams are self-sufficient and have a good mix of product, eng, design, and sales. teams missing any of these disciplines tend not to make a lot of progress.

great builders were often terrible at finding PMF, but a few could iterate their way to something promising

YC continues to be an energetic and optimistic place, and one which is doing a ton of good for the world.

During my time there, I found that YC made me really miss working to start a company from nothing. So, I've decided to stop at a single batch and go back into working deeply on a single problem.

100 mile attempt

Over the past few years, I’ve started running ultramarathons.

My friend Alex first got me into it when he organized a trip to run the “rim-to-rim-to-rim” of the Grand Canyon… which is… exactly what it sounds like. We started at 2am, spent about 18 hours in the canyon, and ultimately traveled 46 miles and climbed 10,000 ft. That experience had me hooked.

I’ve had more free time post-acquisition, so one of my 2021 goals was to run my first 100-miler. I chose the Pine to Palms race up in Oregon, which was originally scheduled for the beginning of September.

My training plan consisted of a weekly cadence which gradually ramped…

Mon/Fri: rest days

Tue, Wed, Thu: build on weds and taper (4/10/6 mi)

Sat/Sun: back to back long runs (30/20 mi)

I didn't fully hit plan, but I was more or less running a marathon every Saturday, and doing about 5,000ft of vert up in the Marin Headlands.

As race day neared, I began to worry. It was peak fire season, and I was not looking forward to spending 28-36 hours outside in 200+ AQI. Lo and behold, the organizers didn’t want that either, so the race was canceled 5 days before the start of the event.

I started to look at other races and didn’t find a lot of options. So, I put together my own race. I tried to mirror the total elevation of pine to palms (20k ft) up in the trails I knew in and out.

I started around 5am at Golden Gate Bridge, and I called it quits when I returned to the bridge 24h in at the 75mi mark. By that point in time the fog was making it tough to see more than a few feet in front of me and I was having trouble keeping food down.

A lot of people ask me why I like running such long distances. I'd say there are two reasons.

The first is that running long distances creates an incredible connection between mind and body. I’ve become much more aware of how I’m feeling physically and mentally on any given day… because I’ve had to!

The other reason is that ultras are great prep for life. Going into a long race, I always know that there will be low points. But I know if I keep going through those low points, I'll eventually come out the other side. They are the ultimate reminder that with enough persistence, you can do very hard things (this holds true in startups as well).

Since this summer, running has now become a core part of my life. I haven’t been able to run for a whole eight weeks due to foot issues. It’s driving me up the wall.

NYC

We moved to NYC in October!

Why move? Mostly for a change of pace.

I'd been in the Bay Area for 10 years up until this point. I've explored most of the streets and parks, settled into a rhythm of favorite restaurants, and generally know what to expect on any given day. It was time for a change.

In the two months I've been here, I've really enjoyed it. On any given night, there's an energy that makes you feel like you could end up anywhere. The food and art are both world class. While tech has a good presence there, it's not the only game in town.

In terms of unexpected surprises of NYC, I've been very pleased with the dynamism here. The street outside our apartment is several centuries old, and it just was re-paved. The restaurants of the West Village have exploded onto the street with a myriad of outdoor dining options. Each one is filled with lights and music. The subway can take you anywhere with a tap of your phone.

As a person who is pro-denser-housing, I've loved seeing new buildings shoot up and unused warehouses turn into flourishing apartment complexes. I don't know much about the local politics, but NYC doesn't seem to have the political baggage you'd find in SF in this dimension.

I still miss the people, the pure density of tech, and exploring the hills of Marin. But I'm excited for a new city.

I'm going to be out here for a year. If you'd like to meet up, shoot me a note.

Fusion and Energy

Recently I've been getting very excited about Fusion energy. After some preliminary research, I'm generally convinced that fusion will be a real technology in our lifetimes, and it will be our best long-term source for clean, limitless electricity.

Before I go further, let that sink in for a minute. Nearly everything that uses energy today–transportation, building materials, growing crops, electricity–has the potential to become 10x cheaper in the next 20-25 years. Direct Air Capture becomes financially feasible. We can Terraform and setup farms in tight spaces. We can access fresh water anywhere on earth.

I believe that cheap energy is one of the best levers we have to reducing global poverty, and solve the productivity paradox that's existed since the 1980s.

I've been getting deep into fusion, but since this post is already lengthy, I'll limit it to a few high-level concepts.

Today, most people are familiar with nuclear fission power. Anytime someone uses the word "nuclear power" today, they're most likely talking about fission.

Fission works just like it sounds. It involves breaking apart heavy, radioactive molecules into lighter ones. The heavier molecules are substances like Uranium or Plutonium. Exposing them to a little bit of energy (typically some neutrons) causes them to decay into smaller molecules.

Typically the smaller molecules have less mass than the original heavy molecule, and the difference is released in energy (Einstein's famous e=mc2). Energy in today's Light Water Reactors is converted to electricity by heating water into steam, and then driving a turbine.

Fusion is the exact opposite process. Fusion takes two light molecules (say Hydrogen) and "fuses" them together by bringing them into very close contact. When the two molecules fuse, some of their mass is lost and converted directly into energy (again, e=mc2). Unlike a chemical reaction, they form a fundamentally new molecule (e.g. Helium).

Sidenote: Iron-56 is at the mid-point of these two processes. It has the lowest mass per nucleon, so it is unable to undergo fusion or fission without taking in more energy. It's a common "end-state" as the universe expands, and this is the reason that both the sun and earth's core are pure iron!

There are two forces that govern nuclear physics...

Coulombic force: this causes protons to repel one another because they are both positively charged. The Coulombic force decays relative to the square of the two objects, so the closer they get, the more they repel at an exponential rate.

Strong nuclear force: this causes protons and neutrons to bind together. It's what holds all molecules together and keeps them from spontaneously breaking down. The strong nuclear force is incredibly strong, but only works under exceptionally short distances (the width of one proton).

What that means is that we have to get neutrons and protons very close together and colliding at high speeds in order to get fusion to occur, so the strong nuclear force overwhelms the Coulombic force.

You may have heard that fusion is "always 20 years away", but fusion isn't a new technology. We've been doing experiments with fusion since the Manhattan project.

While we've generated fusion energy, we've mostly turned it into uncontrolled releases of heat or radiation. We've fallen short at creating a self-sustaining energy that generates more electricity than we put in (fusion researchers refer to net energy gain as Q>1).

Thirty-five years ago, a bunch of the world nuclear powers came together to make fusion a reality. They kicked off a project called ITER which would build the world's first breakthrough fusion reactor. Designs for the reactor started way back in 1992. The project has been under construction since 2007, and the goal is to generate the first plasma by 2025 with actual fusion generation by 2035.

It turns out that in the past 20 years, there have been a bunch of promising new fusion-related efforts, mostly due to better computer simulations (we've come a long ways since 1992) and startups who are able to experiment with fusion more cheaply.

A few of the front-runners I've stumbled across...

Commonwealth Fusion – MIT-spinout which is pursuing a similar strategy to ITER using a Tokamak reactor, but building at a smaller scale. They just hit a large milestone in terms of the magnetic field they can generate (20T).

Helion – using a new technique called a field reversed configuration to accelerate two plasmas towards one another. They have hit a plasma temperature of 100m degrees C.

General Fusion – building a new design which contains plasma within molten metal and a bunch of pistons which confine the plasma, and then capture energy from it, sort of like an internal combustion engine.

There is still a long road ahead for fusion, both from a regulatory perspective and a technology perspective. But all that said, I am incredibly excited to work towards a future where electricity is "too cheap to meter".

Articles

I've been a little bit behind on writing this year. YC dominated my time over the summer to share learnings and lessons, and I poured most of my extra cycles into office hours for founders.

Recently I put out a post based upon my observations of founder pitches at YC: High Bitrate People.

I'm hoping to put out a few more long-form articles in the coming weeks, stay tuned.

Reading

Running all the time meant that I was able to read (or listen to!) a lot more books as well. My notes are here…

Currently I'm reading An Elegant Puzzle (thanks to Albert for the rec, wish I'd read it earlier!) and The Ride of a Lifetime.

Next up, Where's my flying car?.